Broach the subject of transportation planning and traffic engineering with nearly anyone and they, anticipating a barrage of boring facts and geeky analysis, will hastily prepare for a deep mental hibernation.

Well, I’m here to tell you that discussions about traffic can be quite engaging! See for yourself in this wonderful video of a presentation given by Ian Lockwood recently in Portland, posted by Metro.

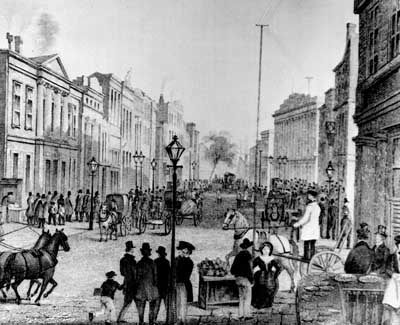

One of the points Ian makes in his talk is illustrated by this drawing of Wall Street circa 1867: streets were not always places that we evaluated solely based on throughput of vehicles!!

The grid was a place of infinite exchanges, sights, smells, and sounds — business was conducted, kids played, you met your neighbor, you grabbed a coffee, food was cooked… . In modern times, many cities have ceded control of their streets, some of their most valuable real estate when it comes to making places compelling and interesting, and turned them over to traffic engineers. Complex computer modeling tools are then used to figure out how to move cars efficiently through town. These models tell us nothing about livability, or foot traffic, or retail viability, or downtown decay…

A good example of the impact that streets can have on a downtown is pictured below. Eugene, during the “urban renewal” heyday of the ’60s and ’70s, ripped out many of their older buildings and then installed wide one-way streets, creating a ring of pavement encircling their downtown, effectively routing people around the gem of a core that still exists near the intersection of their historic main streets.

Most small- to mid-size cities have no idea the impact that uni-directional traffic can have on their downtown cores. These streets are not designed to take you “to” a place, they are designed to route you “through” a place. For the 10% to 20% gain in throughput, a city gets a confusing downtown grid that is difficult to navigate for anyone who is not on an established route. Drivers are not encouraged to stop, experience, and look around, causing retail decline. Cars travel faster, creating an environment that doesn’t encourage pedestrianism, which causes retail decline. And, these one-way roads foster architectural form that does not contribute to effective placemaking, causing retail decline.

It is no surprise then, that the vast majority of Portland’s successful commercial corridors are on two-way streets in neighborhoods with architectural form and density that was constructed in the streetcar era.

{ 0 comments }